Chapter 10 Investigating the impact of the 2005 change in BCG vaccination policy using a fitted dynamic transmission model of TB

10.1 Introduction

In the previous chapter I outlined a model fitting pipeline and discussed the results from using it on the model developed in Chapter 8. Whilst this fitted model may be used to explore the epidemiology of tuberculosis (TB) in the early 2000’s it does not - as currently stands - explore the impact of the 2005 change in BCG vaccination policy (Chapter 2). Models are useful in this context as dynamic model forecasts can be derived for multiple scenarios that may only exist on paper and so have little to no data to support them. These forecasts may then be used by policy makers as indicators of the likely impact of these scenarios.

This chapter details the approach used to extrapolate 1000 samples from the posterior distribution of the fitted model from the previous chapter (for the best fitting scenario with variability in both transmission and non-UK born mixing) beyond the change in BCG policy in 2005 and into the future. It first outlines the scenarios considered, then details the assumptions used to expand the time horizon of the model. Finally the impact of each scenario is explored over multiple time horizons. As discussed in the previous chapter these findings are preliminary in nature, meaning quantitative conclusions cannot be drawn and qualitative conclusions must be appropriately caveated.

10.2 Methods

10.2.1 Scenarios considered

I considered three scenarios from 2005 on-wards. These were:

- Universal BCG vaccination of those at school-age continued with the same coverage as previously.

- Universal BCG vaccination of those at school-age was phased out in 2005 and replaced with universal BCG vaccination of neonates with the same coverage levels as assumed for the BCG schools scheme.

- Universal BCG vaccination of those at school-age was phased out in 2005 (i.e no vaccination post 2004).

The BCG policy change in 2005 was from universal school-age BCG vaccination to targeted vaccination of high risk neonates. However, here universal vaccination of neonates is used as a proxy for targeted vaccination of high risk neonates. This was necessary because the high risk population was not modelled in the model developed in Chapter 8 due to the lack of data on which to base key assumptions. No vaccination was used as a baseline in order to explore the absolute impact of vaccination. Vaccination coverage was assumed to be constant across all scenarios as there was little data on which to base between assumption variation. Regardless of the scenario considered it was assumed that school-age vaccination was in place from 1953 through to 2004.

10.2.2 Forecasting assumptions

Data on non-UK born cases, which were imported into the model via the force of infection (Chapter 8), were not available beyond 2015. To account for this an, age and year adjusted, Poisson regression model was used to forecast future TB incidence in the non-UK born with age treated as a categorical variable. As for years with data, uncertainty was introduced into these forecasts by assuming that non-UK born incidence rates were scaled using the fitted measurement error and normally distributed with a standard distribution based on the fitted measurement standard error (Chapter 9).

As outlined in Chapter 8, births from 2015 on-wards were based on projections from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Age-specific mortality rates were estimated for 2016 on-wards using ONS estimates from 1981-2015, and an exponential model (Chapter 8). Both births and age-specific mortality rates were assumed to have a normal distribution with a standard deviation of 5% of the predicted value. It was assumed that all other parameters were unchanged from the values estimated for 2000-2004 (Chapter 9).

10.2.3 Analytical methods

Estimated age-stratified, and aggregated, TB incidence, and mortality were compared both visually and numerically from 2005 through to 2040 for each scenario. Multiple time horizons were evaluated across this timespan as initially the impact of any policy change may be masked by the large reservoir of vaccinated individuals in the population and because of the impact of the assumed decrease in non-UK born cases over time.

10.3 Results

All results presented in the following section are based on 1000 samples from the posterior distribution of the fitted model from the previous chapter (for the best fitting scenario with variability in both transmission and non-UK born mixing) extended beyond the change in BCG policy in 2005 using the assumptions detailed in the previous section. These results should be considered preliminary because of the low quality of fit achieved in Chapter 9. This means that quantitative estimates are unlikely to be accurate. However, the underlying changes in dynamics caused by vaccination may be used for insight into the likely impact of each scenario and therefore there is still some value in exploring these results.

10.3.1 Forecasting the long-term impact of each vaccination scenario.

Continuing with school-age vaccination resulted in the fewest number of cases regardless of the time-span considered (Table 10.1). However, the difference between vaccination scenarios was consistently small when compared to the overall number of cases. In all scenarios TB incidence was forecast to decrease over time in line with the decreases assumed in non-UK born TB incidence. The lower bounds for each scenario were relatively comparable, with the upper bounds being being higher for both neonatal BCG vaccination and no BCG vaccination when compared to school-age BCG vaccination.

| Year | School-age BCG (95% CrI) | Neonatal BCG (95% CrI) | No BCG (95% CrI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 766 (347, 1419) | 757 (321, 1420) | 757 (326, 1552) |

| 2010 | 735 (344, 1369) | 856 (376, 1516) | 908 (415, 1729) |

| 2015 | 649 (283, 1234) | 757 (311, 1379) | 800 (343, 1547) |

| 2020 | 594 (239, 1124) | 691 (277, 1260) | 737 (297, 1425) |

| 2025 | 537 (203, 995) | 614 (236, 1144) | 659 (250, 1268) |

| 2030 | 488 (178, 925) | 554 (198, 1029) | 594 (213, 1171) |

| 2035 | 442 (155, 845) | 501 (157, 926) | 538 (177, 1034) |

| 2040 | 403 (135, 775) | 453 (134, 849) | 486 (155, 961) |

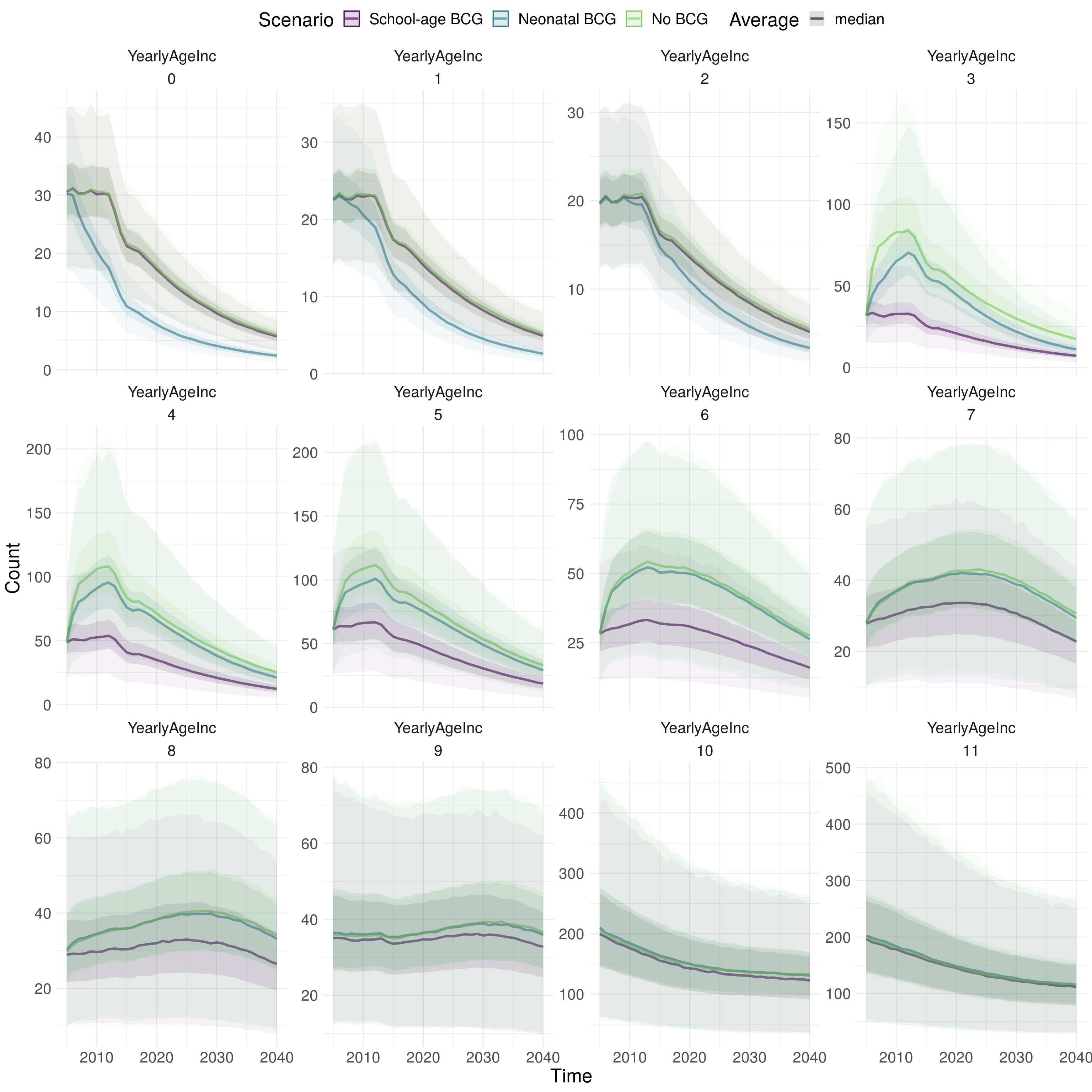

As expected neonatal vaccination resulted in a rapid decline in TB incidence in 0-4 year olds and a smaller but still large reduction in 5-9 year olds (Figure 10.1). There was a slight reduction in 10-15 year olds. School-age vaccination resulted in lower incidence in all adult populations when compared to any other scenario, except in adults over 45 where all scenarios were comparable. Neonatal vaccination resulted in a slight decrease in TB incidence rates when compared to no vaccination in young adults.

Figure 10.1: Forecast of TB incidence for each scenario evaluated from 2005 to 2040, stratified by age group (0-11). 0-9 refers to 5 year age groups from 0-4 years old to 45-49 years old. 10 refers to those aged between 50 and 69 and 11 refers to those aged 70+. Scenarios are differentiated by colour. The darker ribbon for each colour identifies the interquartile range, whilst the lighter ribbon indicates the 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles. The line represents the median. Using 1000 samples from the posterior distribution of the fitted model for the scenario with variability in both transmission and non-UK born mixing.

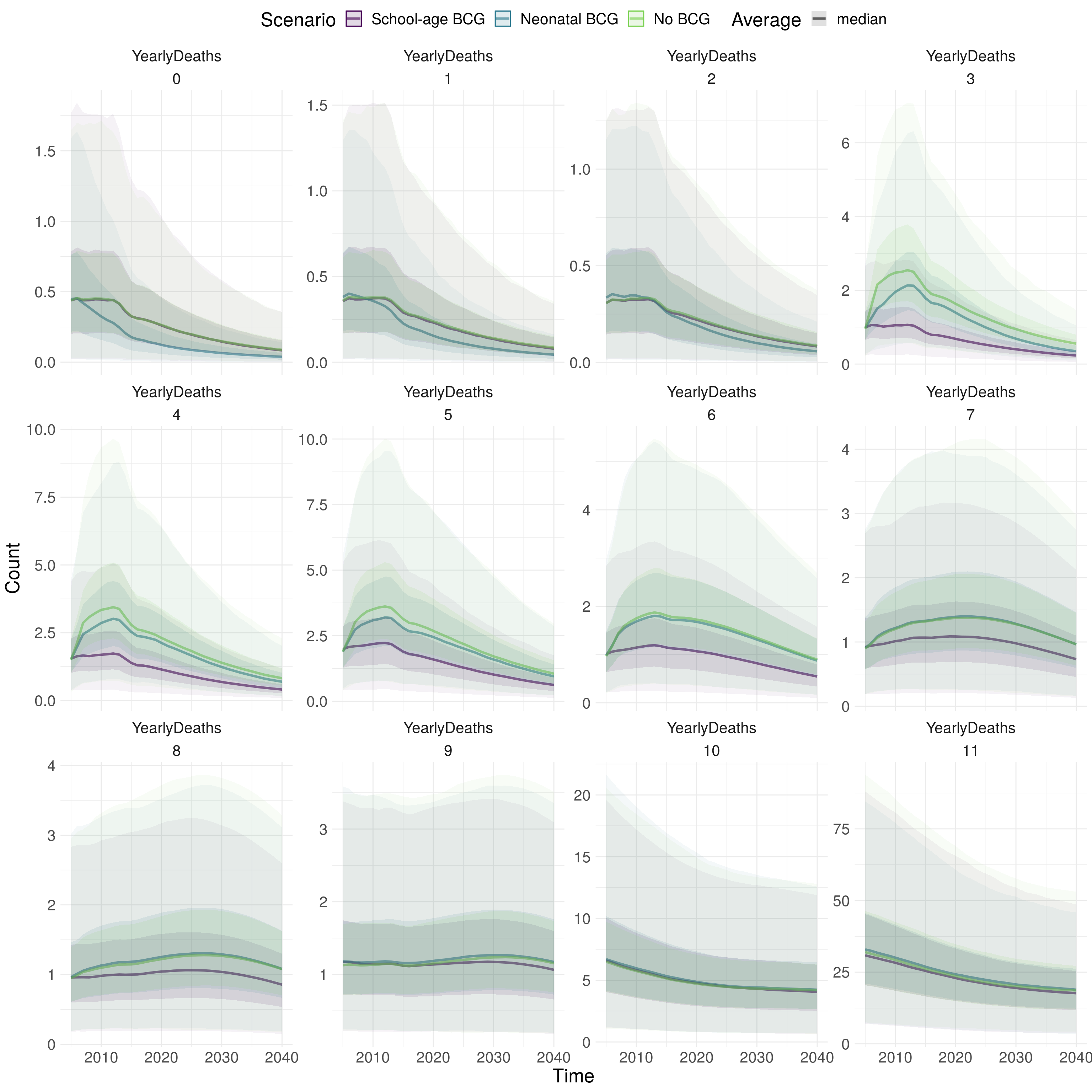

As estimates of TB mortality were low (significantly lower than estimated using the observed data) the impact of any vaccination scenario was minimal (Table 10.2; Figure 10.2). Continuing school-age BCG vaccination resulted in a very small reduction in TB mortality compared to any other scenario (Table 10.2). The age distributed impact of each scenario on TB mortality was comparable to that observed for TB incidence (Figure 10.2).

| Year | School-age BCG (95% CrI) | Neonatal BCG (95% CrI) | No BCG (95% CrI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 51 (16, 119) | 51 (14, 128) | 50 (15, 136) |

| 2010 | 48 (15, 110) | 52 (16, 130) | 53 (17, 146) |

| 2015 | 43 (13, 101) | 47 (13, 119) | 48 (15, 133) |

| 2020 | 39 (11, 92) | 43 (12, 107) | 43 (13, 120) |

| 2025 | 35 (10, 84) | 39 (10, 96) | 39 (11, 108) |

| 2030 | 32 (9, 79) | 35 (9, 89) | 36 (9, 99) |

| 2035 | 30 (8, 74) | 33 (8, 82) | 33 (8, 90) |

| 2040 | 28 (8, 70) | 31 (8, 76) | 31 (7, 83) |

Figure 10.2: Forecast of TB mortality for each scenario evaluated from 2005 to 2040, stratified by age group (0-11). 0-9 refers to 5 year age groups from 0-4 years old to 45-49 years old. 10 refers to those aged between 50 and 69 and 11 refers to those aged 70+. Scenarios are differentiated by colour. The darker ribbon for each colour identifies the interquartile range, whilst the lighter ribbon indicates the 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles. The line represents the median. Using 1000 samples from the posterior distribution of the fitted model for the scenario with variability in both transmission and non-UK born mixing.

10.4 Discussion

In this chapter I outlined 3 vaccination scenarios to explore: continuing school-age BCG vaccination; universal neonatal vaccination; and no further vaccination. For each scenario I forecast TB incidence and TB mortality from 2005 through to 2040 assuming that non-UK born incidence rates would follow the same age stratified trends observed between 2010 and 2015. Although the results presented here are only preliminary, due to the quality of the model fit, it appears that continuing school-age BCG vaccination would have resulted in slightly reduced TB incidence across all time-points considered compared to any other scenario. Neonatal BCG vaccination resulted in reduced TB incidence and mortality in young children but had little impact later in life with a comparable effect to no vaccination. School-age vaccination had no impact on young children but did reduce TB incidence and mortality for all adults up to 45 years old. Beyond 45 years old no scenario impacted TB incidence or mortality.

The model developed in Chapter 8 was motivated by existing theory and robustly parameterised to the available data. It represents the only (known) open-source model of TB transmission and BCG vaccination. However, the model fitting pipeline developed in Chapter 9 did not produce a good fit to the observed data. Ad-hoc model calibration (as discussed in Chapter 9) failed to significantly improve on this fit. This means that the findings presented in this chapter can be considered as indicative only. However, these findings still represent the only modelling study of TB dynamics after a large scale change in BCG vaccination policy. The lack of data to support modelling the high-risk TB population population meant that targeted vaccination of high-risk neonates could not be considered as a scenario. This means that the results presented in this chapter do not contain the vaccination policy that is currently in place and so findings from the model cannot be directly compared to observed incidence data. However, only considering scenarios that alter the age of those vaccinated, rather than both the age of those vaccinated and the targeting of the vaccine, make understanding the impact of changes in vaccination policy easier to determine. The forecasts presented in this chapter are highly sensitive to the forecasted number of non-UK born TB cases. Whilst the regression method outlined in this chapter extrapolates based on current age-stratified trends it may be the case that this extrapolation breaks down over the long - or short - term. To a lesser extent the forecasts presented here are sensitive to the projected number of births and mortality rates. This is particularly the case for incidence rates in neonates and in older adults.

To my knowledge, there are no other dynamic modelling studies evaluating the use of the BCG vaccine in low burden settings that include a comparable level of detail and that are robustly parameterised based on the latest evidence. Harris et al. recently reviewed mathematical models that explored the epidemiological impacts of future TB vaccines.[100] They found that vaccines targeted at all-ages or at adolescents/adults were more effective at eradicating TB than neonatal programmes when vaccine effectiveness was not assumed to degrade with age. These findings agree with those presented in this Chapter, with fewer overall cases observed when vaccination continued in those at school-age, compared to neonatal vaccination. However vaccination in neonates did lead to a decrease in incidence in children both over the long - and short term - in comparison to vaccination at school-age.

The results presented in this chapter generally agree with other findings from this thesis. In Chapter 7, which estimated the impact of the change in vaccination policy in those directly impacted by it, there was some evidence that changing to neonatal vaccination was associated with a small increase in incidence rates in those who were school-age. There was less evidence of a reduction in incidence rates in UK born neonates. The first of these results matches the findings presented here. However, this chapter estimated a rapid reduction in TB incidence in young children which was not seen in the previous work. Chapter 5, which recreated a previously published transmission chain model estimated an initial impact from ending school-age BCG vaccination but that this impact would decline with time. The results presented here agree with this findings as long as it is assumed that non-UK born incidence will decrease over time. However, here the impact of the scheme was estimated to continue beyond the 15 year time horizon estimated in Chapter 5. In Chapter 6 I found some evidence that BCG vaccination may decrease all-cause mortality in TB cases and some evidence that indicated that this may be related to reduced TB mortality. If either of these associations were causal then they would increase the benefit of vaccination scenarios compared to no vaccination but would not alter the trade-offs between neonatal and school-age vaccination.

Further work is need to improve the fit of the model to observed data (Chapter 9). This will result in improved forecasts and more reliable results. In addition, other vaccination coverage scenarios could be considered that explored the impact of vaccinating a reduced proportion of both those at school-age and neonates. If additional data becomes available, or if the appropriate assumptions are used, the inclusion of the high-risk population into the model would allow the evaluation of targeted high-risk neonatal vaccination in comparison to the other scenarios considered here. The extrapolation of the trend in non-UK born cases is a limitation of this model and as such should be further explored using other assumptions such as constant non-UK born cases, incidence rates based on expert opinion and estimates based on other global modelling studies.

The results presented here indicate that changing from a school-age BCG vaccination programme to a neonatal BCG programme lead to an overall increase in TB incidence, with increases concentrated in the young adults, and to a lesser degree, in older adults. Neonatal vaccination led to a decrease in TB incidence in children both in the short - and long term. This indicates that direct vaccination provides the best protection for children rather than indirect protection via reduced transmission. This finding is likely to be dependent on the degree of background transmission and so further modelling studies are needed in diverse settings before conclusions can be generalised. No vaccination was shown to lead to increased incidence in all age-groups when compared to school-age vaccination and in children only when compared to neonatal vaccination. The impact of any vaccination programme on older adults was small. These results are preliminary in nature as the model on which they are based fitted poorly to the observed data. However, they do indicate some of the trade-offs involved in setting BCG policy. If reducing childhood incidence was a goal of the 2005 policy change then these results indicate a clear success. On the other hand if reducing overall TB incidence was the goal then stopping shool-age vaccination has not been a success.

10.5 Summary

- Continuing school-age vaccination results in lower overall incidence rates compared to both neonatal vaccination, and no vaccination.

- Neonatal vaccination resulted in low incidence in children compared to any other scenario.

- No vaccination led to higher incidence in all age groups when compared to school-age vaccination and in children only when compared to neonatal vaccination.

- The impact of any vaccination on cases in older adults (50+) was small.

- These results are indicative only due to poor quality of model fit achieved in the previous chapter (Chapter 9).

References

100 Harris RC, Dodd PJ, White RG. The potential impact of BCG vaccine supply shortages on global paediatric tuberculosis mortality. BMC Med 2016;14:138.